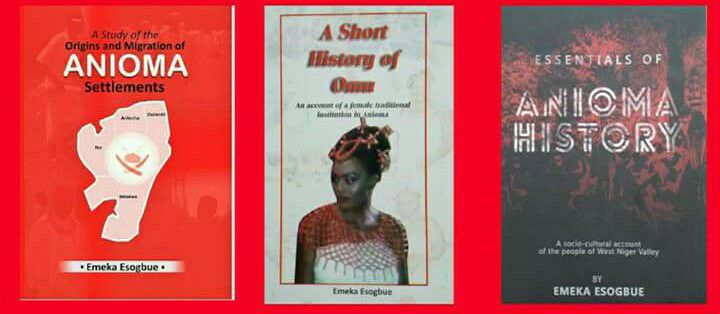

At the lobby of a hotel in Asaba, Delta State, Nigeria where I had taken my two teenage sons to, a few years back, for an Anioma art exhibition as part of our occasional family cultural homecoming, laid a copy of a magazine ‘Anioma Essence’. A read, piece by piece of the articles contained in the magazine, was my first encounter with Emeka Esogbue, editor of the magazine. On further enquiry, the ‘Pen Master’ as he turned out to be known and fondly called, is my Isieke-Umuekea Village kinsman in Igbuzo, a historian and avid writer. A Diaspora friend and kinsman of the Enuani (Anioma) stock based in the United States of America would later do me the pleasure in July 2017 of presenting me a Birthday gift; a book entitled ‘Essentials of Anioma History’ by no other than the Pen Master himself. I have since enlarged my list of prospective books acquisition to enrich my personal library to include other works of the Pen Master, which I had earlier borrowed and read. These are: “A Study of the Origins and Migrations of Anioma Settlements” and “A Short History of Omu”.

Being away from home for more than two decades and half, one begins to suffer what National Geographic Society’s Explorer-in-Residence Wade Davis called the “erosion of the ethnosphere.” Along with language, one also begins to lose touch with the arts, crafts, vocational skills, folklore, and customs of his traditional and indigenous peoples. Works such as those by Emeka Esogbue are for me a means of staying connected to my Igbuzo, Anioma heritage. Despite best efforts, the longer you are away from home the more the propensity for the culture, history and heritage to erode you. Ironically for me, my appreciation of the same heritage grows more at the same time. Next to Nna, my father and living encyclopedia of Igbuzo history, I have found the works of Emeka Esogbue immeasurable sources of knowledge of not only our history but also our traditions and customs. I would always dip into his work to arm myself for my numerous discussions and debates with my sons, now in their early twenties, who remain eager to sort out the cultural conflicts that come with been born abroad yet connected deeply to your roots. I would always tell them especially when I appear to be losing the debate to commonsense that you can’t logically disagree with something or an issue that you have no firm grasp of. The works of Emeka Esogbue help me to grasp the essence of the Igbuzo, Anioma history. I disagree with some isolated aspects of the customs but understanding them help me appreciate them. This is to a large extent because in his writings, Emeka Esogbue does not simply chronicle them as most historians before him would do, he interprets them.

Emeka Esogbue deploys a writing style that is refreshing. He is first and foremost a historian. Reading records is therefore his point of departure. But what he does with the records actually marks him out from his peers. He is far from what I refer to as ‘historian of chronicles’ where a report is simply given on what a historian finds and informs the wider world about the past usually arranged in chronological order and providing no further comments or discussions.

I guess what I find most invaluable in the work of Emeka Esogbue is his uncommon realization that historical records that survive for most periods of history are both incomplete and often contradictory. Take the case of the origin of the people of Igbuzo as example. The Pen Master’s position on this important issue is perhaps the most intelligent attempt so far in addressing the gaps and contradictions in the existing accounts. His interpretative skills in addressing historical gaps and contradictions have placed him a notch above his generation of historians and authors.

Collins NWEKE

Discover more from A Fairer Europe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.